21 December, 2015

Psychologists discover the truth of an old conservative saying

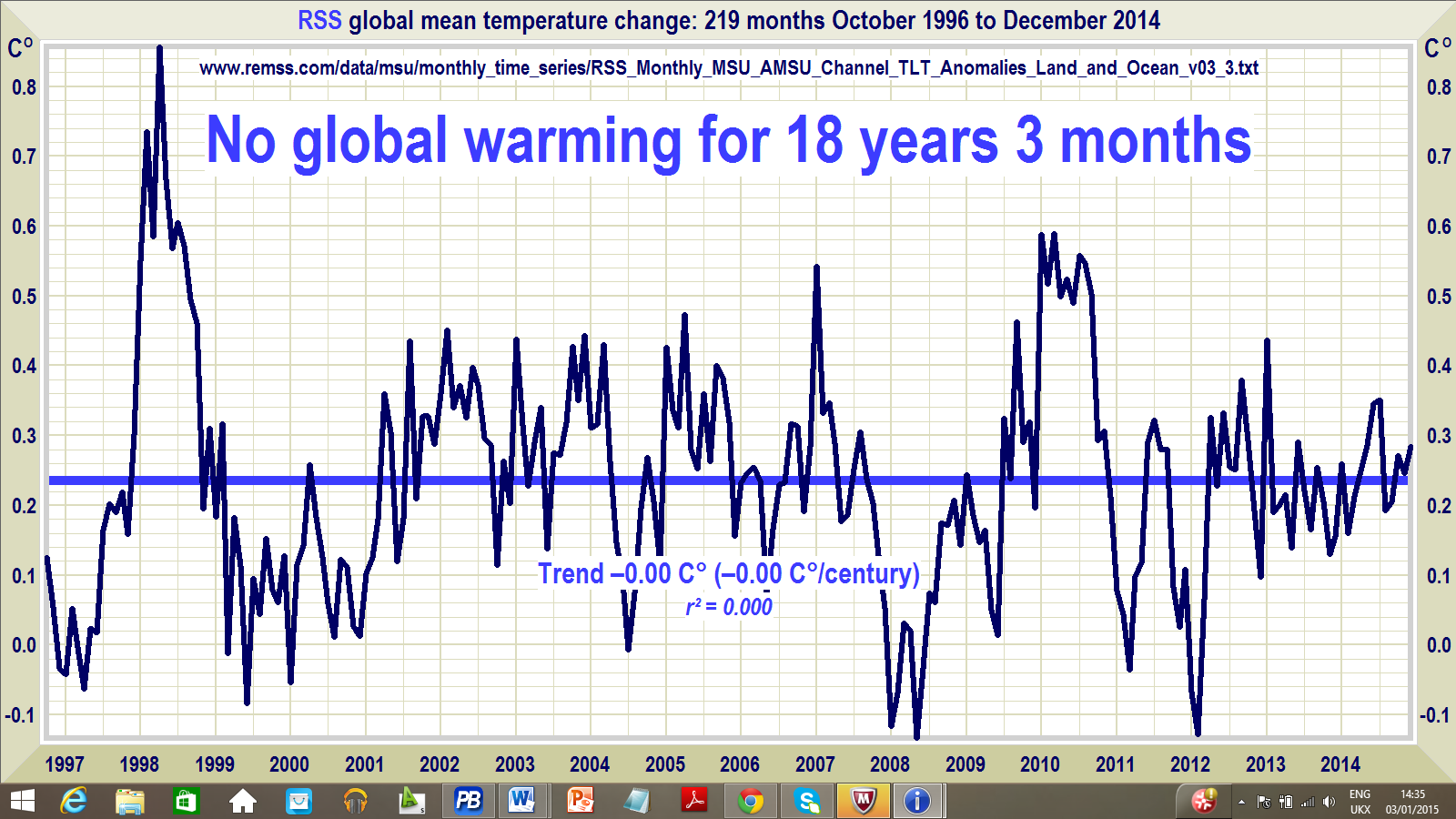

The saying is "A conservative is a liberal who got mugged last night". It is of no certain origin but is often attributed to Irving Kristol or some other NYC neoconservative -- though it is also attributed to Frank Rizzo, who rose from police chief to Mayor of Philadelphia. The point is of course the notoriously poor reality contact of liberals. Most of what they believe is at variance with reality, with "all men are equal" being the most obvious example plus global warming and most of feminism being other examples. Here's that pesky graph of the satellite temperature record again:

And the wisdom of the "mugged" saying was shown in the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, when attitudes among American adults were shown to have shifted Rightward after the attacks. The attacks may be said to have "mugged" America, at least temporarily.

A new article (below) extends the finding to Britain -- concerning the time in 2005 when Britain had its big attack by Muslim terrorists. And the interesting thing this time is that it was ONLY liberals who changed their attitudes. By 2005, British conservatives had learned from the 9/11 attacks and more or less expected what happened in Britain. But liberals were caught by surprise. They had NOT learned from 9/11. So the attitude change was among British liberals only.

Amusing that the authors below describe heightened caution about Muslims as "prejudice". I would have thought that it was POSTjudice -- evidence of learning, not evidence of hostility

Liberals' attitudes toward Muslims and immigrants became more like those of conservatives following the July 7, 2005 bombings in London, new research shows. Data from two nationally representative surveys of British citizens revealed that feelings of national loyalty increased and endorsement of equality decreased among political liberals following the terrorist attack.

The findings are published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

Terrorist attacks on major international capital cities such as Paris, Ankara, or London are rare and dramatic events that undoubtedly shape public and political opinion. But whose attitudes do they affect most, and in what way?

"Our findings show that terrorism shifts public attitudes towards greater loyalty to the in-group, less concern with fairness, and greater prejudice against Muslims and immigrants, but it seems that this effect is stronger on those who are politically left-leaning than those who are right-leaning," explain psychological scientists from the Center for the Study of Group Processes at the University of Kent.

"The overall impact is to create a climate in which it may be harder to promote or sustain intergroup tolerance, inclusiveness and trust," says Julie Van de Vyver of the University of Kent, one of the authors on the study.

Research from psychological science has shown that people often adopt ideological belief systems that reduce their feelings of threat. Based on these findings, the research team hypothesized that the bombings would cause liberals to shift moral perspectives in favor of protecting the in-group, akin to the values typically reported by political conservatives. They speculated that this shift would ultimately lead to an increase in prejudice toward the out-group among liberals.

Historic survey evidence gathered by two of the study authors, Diane Houston and Dominic Abrams, provided the research team with real-world insight. The researchers analyzed newly available data from two nationally representative surveys, administered about 6 weeks before and 1 month after the July 7, 2005 bombings in London. The bombings, which occurred on public transport, led to the deaths of 52 people and injury of 770 people. The bombings were part of an Al Qaeda attack carried out by three British-born Muslims from immigrant families and one Jamaican convert to Islam.

In the two surveys, participants rated their agreement with statements that represented four moral foundations: in-group loyalty (i.e., "I feel loyal to Britain despite any faults it may have"), authority-respect (i.e., "I think people should follow rules at all times, even when no one is watching"), harm-care (i.e., "I want everyone to be treated justly, even people I do not know. It is important to me to protect the weak in society), and fairness-reciprocity (i.e., "There should be equality for all groups in Britain").

Participants also rated their agreement with statements about attitudes toward Muslims (e.g., "Britain would lose its identity if more Muslims came to live in Britain") and immigrants (e.g., "Government spends too much money assisting immigrants").

As expected, attitudes towards Muslims and toward immigrants were more negative following the attacks than before, but only among liberals; conservatives' views stayed relatively constant. Thus, liberals' attitudes seemed to shift toward those of conservatives following the bombings.

This increased prejudice was accounted for by changes in liberals' moral foundations. Specifically, liberals showed an increase in in-group loyalty and a decrease in fairness, and these shifts accounted for their negative attitudes toward Muslims and immigrants.

The results show that people's moral perspectives aren't necessarily constant - they can change according to the immediate context.

"An important challenge following dramatic terrorist attacks is to know how to engage with public perceptions and attitudes, for example to prevent an upsurge in prejudice and its effects," says Abrams.

"For people working to tackle prejudice, it is important to be aware that terror events may have different effects on the attitudes of people who start from different political orientations," the researchers write.

Based on these findings, the researchers argue that terrorist attacks may ultimately lead conservatives to consolidate their existing priorities, making them resistant to change; at the same time, such attacks may prompt a shift in liberals' priorities toward more prejudiced attitudes.

This shift in attitudes may be reflected in the UK parliament's recent decision, following the November attacks in Paris, to approve bombing missions in Syria—a reversal of its decision in 2013. The researchers note that the greatest change in voting occurred among Labour Members of Parliament, who fall on the left end of the political spectrum; they showed a 20% increase in support for the bombing missions from 2013 to 2015.

SOURCE

Go to John Ray's Main academic menu

Go to Menu of longer writings

Go to John Ray's basic home page

Go to John Ray's pictorial Home Page

Go to Selected pictures from John Ray's blogs