December 31, 2021

Doughnut economics

The ideas of Doughnut economics are pretty woolly but it seems to be catching on in Greenie circles so I want to note a few things about it. I reproduce below some excerpts from a very sesquipedalian article about it to give us the idea of it.

Although its proponents are very vague about it, Doughnut economics can in fact be summarized very simply: prioritize the environment over money. In other words, do things in a way that is better for the environment rather than in ways that are most economically efficient.

Despite its promotion as a "radical new economic theory" it is in fact a very old feel-good idea, and what it has led to -- as set out below -- shows the lack of understanding of the world that it embodies: When we do things in the most economically efficient way, it is not money we are prioritizing, it is human work and effort. Money is just a marker. It tells us how much effort is required to produce a good or service. The are imperfections in the system but that is basically it. Study economics if you want the detail.

So we see the stupidity of some of the actions that are praised below. Instead of buying new computers, they employ people to fix up old ones -- which is very labour-intensive. And in the end you still have an old and limited computer. In terms of human effort the refurbished computer is in fact very expensive. A lot of valuable human effort has been used to produce an inferior product. If we did everything that way, we would have a much reduced availability of goods and services.

The circular economy adds up to a waste of human labour and effort. How is that humane or wise? If the environment really needs saving, there are surely better ways about it

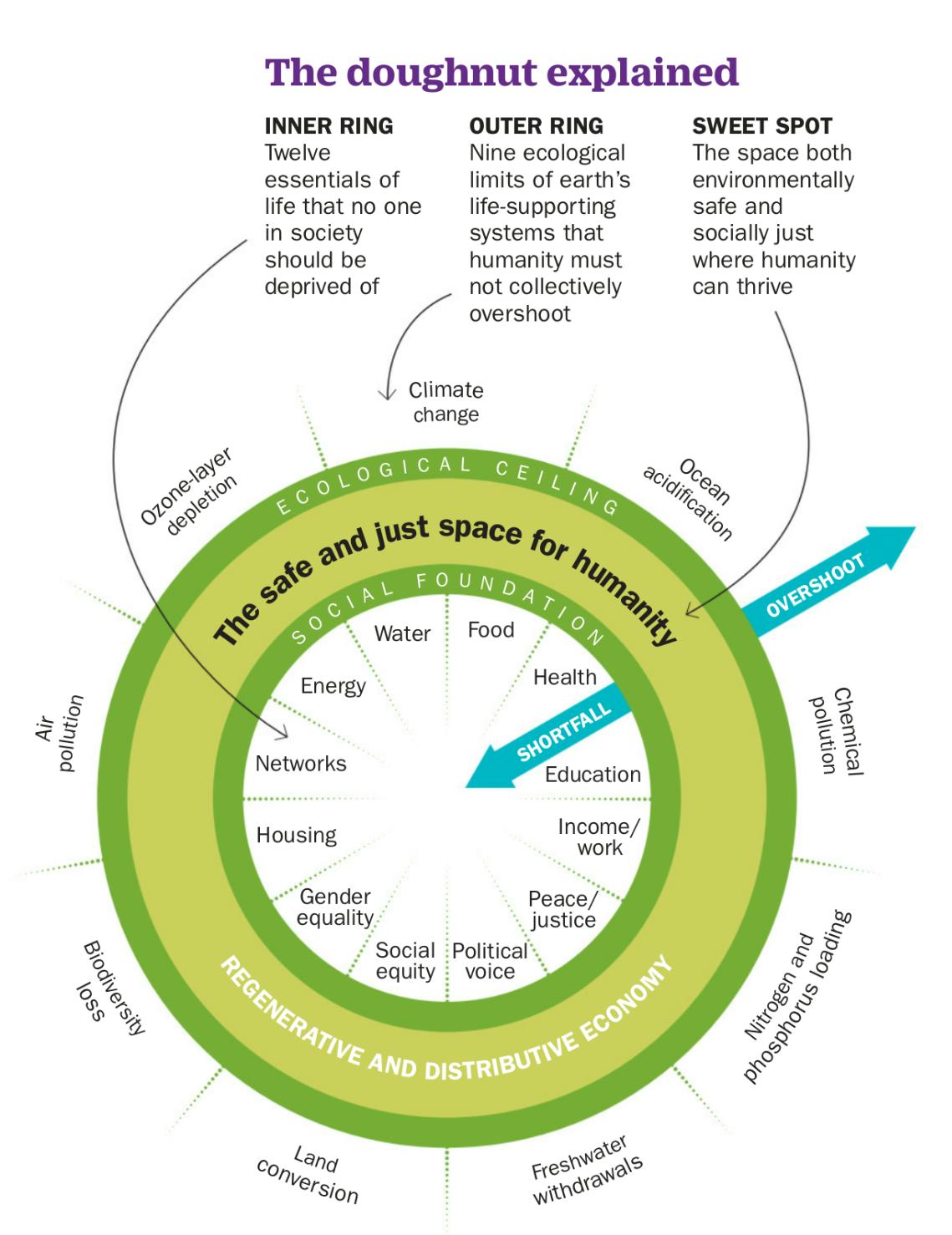

In April 2020, during the first wave of COVID-19, Amsterdam’s city government announced it would recover from the crisis, and avoid future ones, by embracing the theory of “doughnut economics.” Laid out by British economist Kate Raworth in a 2017 book, the theory argues that 20th century economic thinking is not equipped to deal with the 21st century reality of a planet teetering on the edge of climate breakdown. Instead of equating a growing GDP with a successful society, our goal should be to fit all of human life into what Raworth calls the “sweet spot” between the “social foundation,” where everyone has what they need to live a good life, and the “environmental ceiling.” By and large, people in rich countries are living above the environmental ceiling. Those in poorer countries often fall below the social foundation. The space in between: that’s the doughnut.

In 1990, Raworth, now 50, arrived at Oxford University to study economics. She quickly became frustrated by the content of the lectures, she recalls over Zoom from her home office in Oxford, where she now teaches. She was learning about ideas from decades and sometimes centuries ago: supply and demand, efficiency, rationality and economic growth as the ultimate goal. “The concepts of the 20th century emerged from an era in which humanity saw itself as separated from the web of life,” Raworth says. In this worldview, she adds, environmental issues are relegated to what economists call “externalities.” “It’s just an ultimate absurdity that in the 21st century, when we know we are witnessing the death of the living world unless we utterly transform the way we live, that death of the living world is called ‘an environmental externality.’” Almost two decades after she left university, as the world was reeling from the 2008 financial crash, Raworth struck upon an alternative to the economics she had been taught. She had gone to work in the charity sector and in 2010, sitting in the openplan office of the anti poverty nonprofit Oxfam in Oxford, she came across a diagram. A group of scientists studying the conditions that make life on earth possible had identified nine “planetary boundaries” that would threaten humans’ ability to survive if crossed, like the acidification of the oceans. Inside these boundaries, a circle colored in green showed the safe place for humans.

But if there’s an ecological overshoot for the planet, she thought, there’s also the opposite: shortfalls creating deprivation for humanity. “Kids not in school, not getting decent health care, people facing famine in the Sahel,” she says. “And so I drew a circle within their circle, and it looked like a doughnut.”

Raworth published her theory of the doughnut as a paper in 2012 and later as a 2017 book, which has since been translated into 20 languages. The theory doesn’t lay out specific policies or goals for countries. It requires stakeholders to decide what benchmarks would bring them inside the doughnut— emission limits, for example, or an end to homelessness. The process of setting those benchmarks is the first step to becoming a doughnut economy, she says.

Raworth argues that the goal of getting “into the doughnut” should replace governments’ and economists’ pursuit of never- ending GDP growth. Not only is the primacy of GDP overinflated when we now have many other data sets to measure economic and social well- being, she says, but also, endless growth powered by natural resources and fossil fuels will inevitably push the earth beyond its limits. “When we think in terms of health, and we think of something that tries to grow endlessly within our bodies, we recognize that immediately: that would be a cancer.”

The doughnut can seem abstract, and it has attracted criticism. Some conservatives say the doughnut model can’t compete with capitalism’s proven ability to lift millions out of poverty. Some critics on the left say the doughnut’s apolitical nature means it will fail to tackle ideology and political structures that prevent climate action.

Cities offer a good opportunity to prove that the doughnut can actually work in practice. In 2019, C40, a network of 97 cities focused on climate action, asked Raworth to create reports on three of its members— Amsterdam, Philadelphia and Portland— showing how far they were from living inside the doughnut. Inspired by the process, Amsterdam decided to run with it. The city drew up a “circular strategy” combining the doughnut’s goals with the principles of a “circular economy,” which reduces, reuses and recycles materials across consumer goods, building materials and food. Policies aim to protect the environment and natural resources, reduce social exclusion and guarantee good living standards for all.

The new, doughnut-shaped world Amsterdam wants to build is coming into view on the southeastern side of the city. Rising almost 15 ft. out of placid waters of Lake IJssel lies the city’s latest flagship construction project, Strandeiland (Beach Island). Part of IJburg, an archipelago of six new islands built by city contractors, Beach Island was reclaimed from the waters with sand carried by boats run on low emission fuel. The foundations were laid using processes that don’t hurt local wildlife or expose future residents to sealevel rise. Its future neighborhood is designed to produce zero emissions and to prioritize social housing and access to nature. Beach Island embodies Amsterdam’s new priority: balance, says project manager Alfons Oude Ophuis. “Twenty years ago, everything in the city was focused on production of houses as quickly as possible. It’s still important, but now we take more time to do the right thing.”

The city has introduced standards for sustainability and circular use of materials for contractors in all cityowned buildings. Anyone wanting to build on Beach Island, for example, will need to provide a “materials passport” for their buildings, so whenever they are taken down, the city can reuse the parts.

On the mainland, the pandemic has inspired projects guided by the doughnut’s ethos. When the Netherlands went into lockdown in March, the city realized that thousands of residents didn’t have access to computers that would become increasingly necessary to socialize and take part in society. Rather than buy new devices—which would have been expensive and eventually contribute to the rising problem of ewaste—the city arranged collections of old and broken laptops from residents who could spare them, hired a frm to refurbish them and distributed 3,500 of them to those in need. “It’s a small thing, but to me it’s pure doughnut,” says van Doorninck.

The local government is also pushing the private sector to do its part, starting with the thriving but ecologically harmful fashion industry. Amsterdam claims to have the highest concentration of denim brands in the world, and that the average resident owns fve pairs of jeans. But denim is one of the most resource intensive fabrics in the world, with each pair of jeans requiring thousands of gallons of water and the use of polluting chemicals.

In October, textile suppliers, jeans brands and other links in the denim supply chain signed the “Denim Deal,” agreeing to work together to produce 3 billion garments that include 20% recycled materials by 2023—no small feat given the treatments the fabric undergoes and the mix of materials incorporated into a pair of jeans. The city will organize collections of old denim from Amsterdam residents and eventually create a shared repair shop for the brands, where people can get their jeans fxed rather than throwing them away. “Without that government support and the pressure on the industry, it will not change. Most companies need a push,” says Hans Bon of denim supplier Wieland Textiles.

Doughnut economics may be on the rise in Amsterdam, a relatively wealthy city with a famously liberal outlook, in a democratic country with a robust state. But advocates of the theory face a tough road to effectively replace capitalism. In Nanaimo, Canada, a city councillor who opposed the adoption of the model in December called it “a very left-wing philosophy which basically says that business is bad, growth is bad, development’s bad.”

In fact, the doughnut model doesn’t proscribe all economic growth or development. In her book, Raworth acknowledges that for low- and middleincome countries to climb above the doughnut’s social foundation, “significant GDP growth is very much needed.” But that economic growth needs to be viewed as a means to reach social goals within ecological limits, she says, and not as an indicator of success in itself, or a goal for rich countries. In a doughnut world, the economy would sometimes be growing and sometimes shrinking.

Still, some economists are skeptical of the idealism. In his 2018 review of Raworth’s book, Branko Milanovic, a scholar at CUNY’s Stone Center on Socio -Economic Inequality, says for the doughnut to take off, humans would need to “magically” become “indifferent to how well we do compared to others, and not really care about wealth and income.”

https://time.com/5930093/amsterdam-doughnut-economics/

This note originated as a blog post. For more blog postings from me, see

DISSECTING LEFTISM,

TONGUE-TIED,

EDUCATION WATCH INTERNATIONAL,

GREENIE WATCH,

POLITICAL CORRECTNESS WATCH, and

AUSTRALIAN POLITICS. I update those frequently.

Much less often, I update Paralipomena , A Coral reef compendium and an IQ compendium. I also put up occasional updates on my Personal blog and most days I gather together my most substantial current writings on THE PSYCHOLOGIST.

Email me here (Hotmail address). My Home Pages are here (Academic) or here (Personal). My annual picture page is here; Home page supplement; Menu of longer writings